This is only a travel post if you consider memory lane to be a destination…

When I was in sixth grade, I discovered writing. Don’t get me wrong: I wrote before then. In fact, I recently found my school journal from third grade and cringed through page after page of descriptions of my favorite color (pink?!?) and my favorite animal (kitten?!?!). But, in sixth grade, my language arts teacher told me that my writing was good, and that got my attention; I wanted to validate her claim and get even better.

I loved that class. My teacher was calm and reasonable and had a haircut like Mary Tyler Moore. She gave us a lot of writing assignments, from partner interviews and mythology stories to poems and essays about family members. At the end of each unit, she would bind everyone’s final works into a booklet, and each of us would get one. I loved coming home and reading all of the stories. Seeing my work in print gave me a sense of accomplishment, and I would be lying if I said I didn’t compare my writing to others’ and feel a bit proud. After a few units, I knew which classmates wrote well, and I respected them.

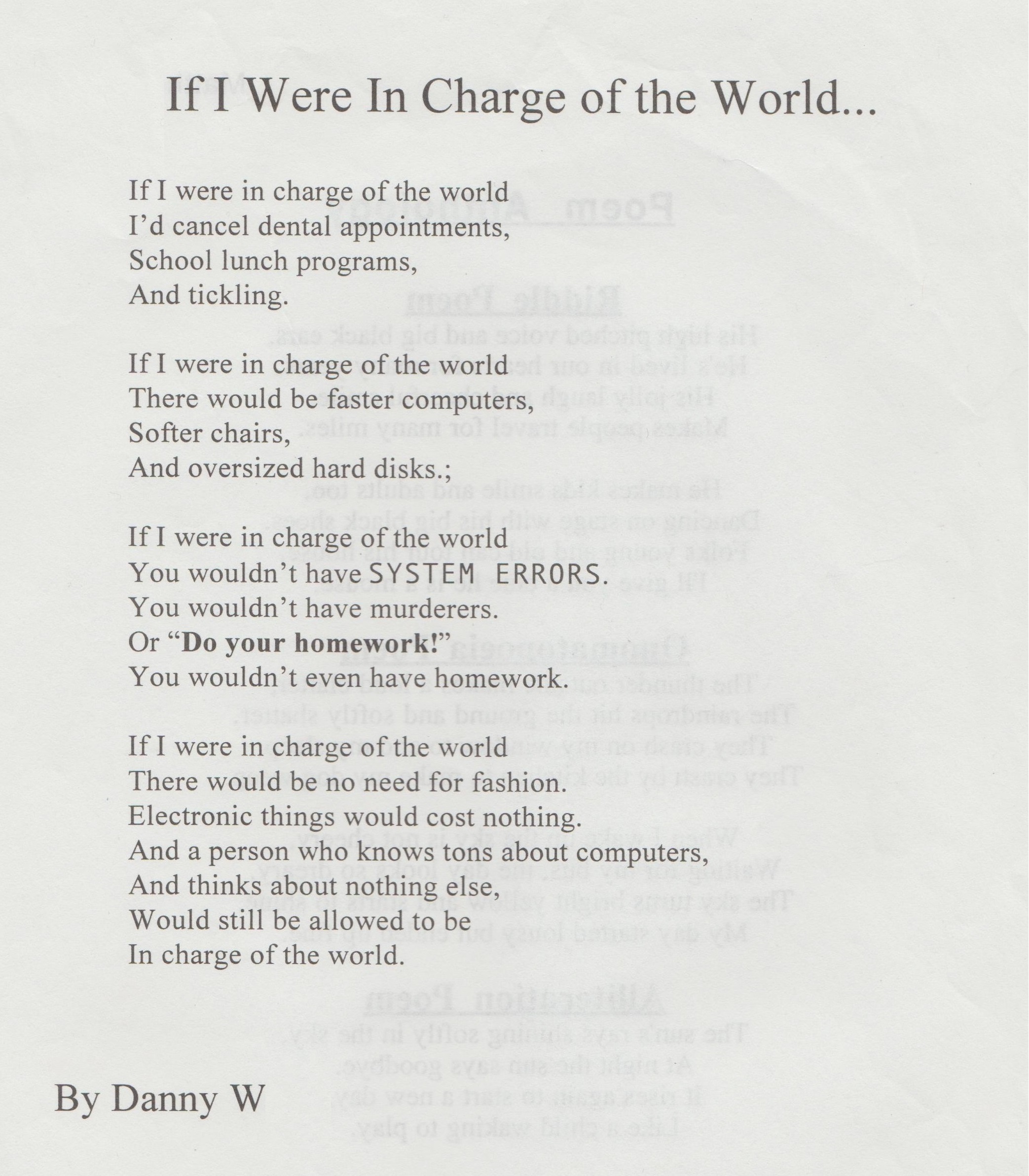

And then, we had an assignment to write poems that started with, “If I were in charge of the world.” I have absolutely no recollection of what I wrote. But I remember another poem in that booklet, and I remember it well enough to quote part of it, twenty years later.

It was written by a boy in my class named Danny, whose writing I had never noticed. Danny was a bit eccentric: not shy, but not interested in the dramas of middle school; passionate about science and computers, and unwilling to hide it; and occasionally clueless. In today’s over-diagnostic culture, perhaps some might say he had Asperger’s. I am neither qualified to comment on this, nor would my twenty-year-old memories be useful as inputs. In either case, I was as polite to him as I was to everyone else, and we co-existed as two ships passing silently in the night.

But his “In charge of the world” poem was different. The rest of us wrote poems that were imaginative and self-aggrandizing and silly. The hopes we listed were an attempt to hold on to our expiring childishness, while simultaneously posturing for our teenage friends. It was like each writer had asked himself, “What is it okay to admit to wanting?” But not Danny.

His poem was honest. It didn’t try to over-complicate things or show off for anyone at all. His wants rang true – even the ones I didn’t understand back then. But more importantly, the last stanza of his poem admitted to a sort of wistfulness over not fitting in. The rest of us were all standing around pretending we fit perfectly, and that we didn’t care about fitting in anyhow. Danny’s words called us out for the liars we were. And they rang in my head for weeks and months afterwards.

His poem didn’t change my writing. I was a teenage girl, and I needed those walls and that pretending. But, in a world before Postsecret and social networks for every niche interest, Danny’s poem made me feel like I wasn’t alone. And that was what twelve-year old me needed most.